by Bridget Flanagan

Ride Away – on new and old roads – Part One

by Bridget Flanagan

I have long been fascinated by the history of the roads and routes in both Hemingford parishes. It’s a huge subject, with the information scattered (and sometimes contradictory), and the early history hard to find - so my research is moving slowly. But for this article and the next I thought I would share some examples of observations gathered so far. We will travel along three roads, starting at the western boundary of Hemingford Abbots.

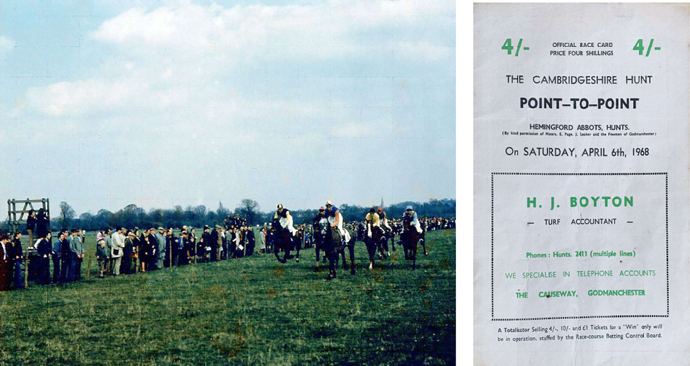

First, a pause for a small historical detour. Some of you may remember the Cambridgeshire Hunt holding its annual point-to-point steeplechase racing on the Godmanchester Common. The event was accessed from the western end of Common Lane and, although not in the Parish, it was given the address of Hemingford Abbots. The meeting was held there from 1957-1971 and the course of about three and a quarter miles was generally regarded as fairly tough. Point-to -point racing is strictly for amateur Hunt riders and the 1968 race card shows five races at the meeting with competitors from all over East Anglia. In 1971 The Cambridge News reported that the meeting, part of Huntingdonshire’s social whirl for almost 20 years would end because part of the course, one of the most attractive in the region, with a quiet riverside setting, is to be quarried for gravel.

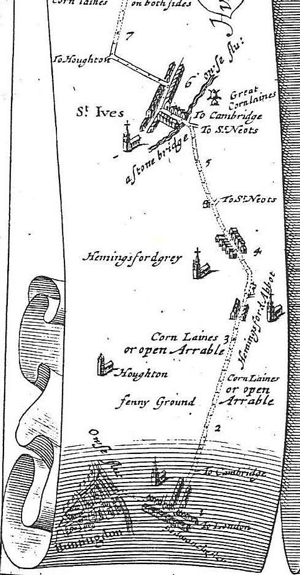

Today Common Lane is a cul-de-sac road. At its western end it adjoins a bridleway that runs westwards across Godmanchester Eastside Common to meet Cow Lane. But 18C and early 19C maps show Common Lane and the bridleway as part of a continuous through route from St Ives and the Hemingfords to Godmanchester. This is a natural route in the river valley – and, as such, very probably an ancient route. (Not unlike the Thicket Path from Houghton to St Ives). It is close to the river but for much of its length is on the slightly higher gravel terraces above most floods. The route passes through and connects old settlements, especially the market towns of Huntingdon and St Ives which are also major bridging points on the Great Ouse. But trying to trace the history of this road using, what might be assumed, an obvious source – maps – is not easy, because roads were (almost) never shown on maps until the late 17C. For example, all county maps of Huntingdonshire, to that date, show (possibly) one road – the Old North Road. But then came a great invention for the traveller. In 1675 John Ogilby published ‘Britannia’ - the first English road-atlas. The concept was new and executed with great simplicity of design. After commissioning extensive surveying he depicted the routes of 73 Main and Cross Roads of England and Wales in strip fashion on a hundred folio sheets. He used a standard scale of one inch to one mile and, very importantly, the statute mile of 1760 yards. (It sounds simple now, but in the 17C cartographers used several different miles).

Ogilby’s brilliant work was quickly copied, and plagiarised, and from then on no regional maps were without roads. ‘His’ roads were drawn on subsequent County maps and even inserted on earlier ones such as those of Saxton and Speed. For today’s historian, the Ogilby routes are those before the ancient roads were abandoned, diverted or altered at either the time of turnpiking of roads or the enclosure of common land.

John Ogilby chose the ‘Road from Huntingdon to Ipswich’ as one of his 73 roads in 1675. He directs the traveller through St Ives, Earith, Ely, Soham, Bury, Woolpit and Needham. On leaving Godmanchester he marks the road south to London – this is the Old North Road following the route of Ermine Street through Royston (today, the A1198 and then part of the A10). The traveller is to turn left, and go past the right turn marked to Cambridge (today, the A1307). Ogilby's route then continues east to St Ives using the road across the Godmanchester Common. There are accompanying instructions: an open way leads you through a small village call’d Hemingsford-Abot, the Church on the Right: and 5 Furlongs farther through Hemingsford-Grey, the Church on the Left.

Yes! You’ve spotted his mistake – he has the church in Hemingford Abbots on the wrong side of the road.

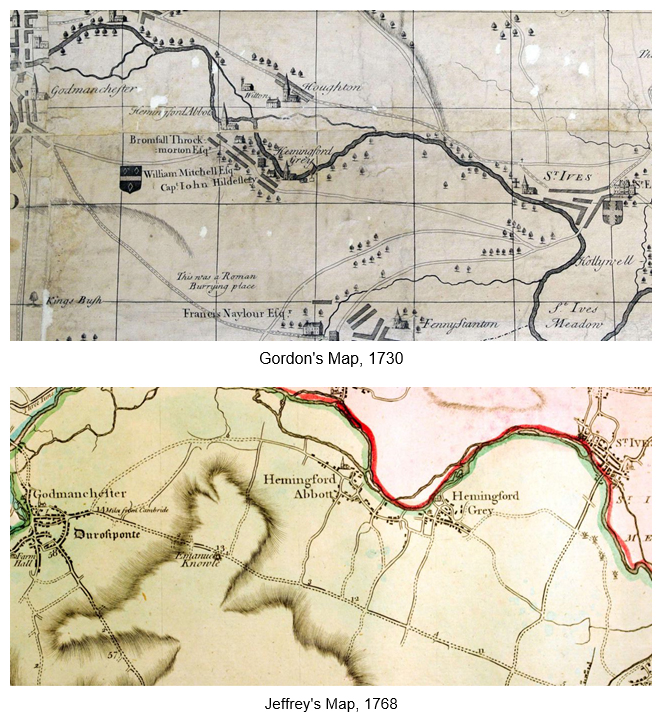

Two 18C County maps continue to show Common Lane as part of a through road across the Godmanchester Common. These are William Gordon’s map of 1730 and Thomas Jeffreys’ map of 1768. (As well as their roads, both of these beautiful maps have a wealth of detail for the historian). Gordon's map was dedicated to the Duke of Manchester and includes all the Lords of the Manors, their coats of arms, their houses/seats (most of which are drawn individually with recognisable architectural features) and whether the parish had a Rector or Vicar. The Jeffreys' map has a more sophisticated representation of topography and uses colour to delineate boundaries and carefully graded hatching to show the contours of the landscape.

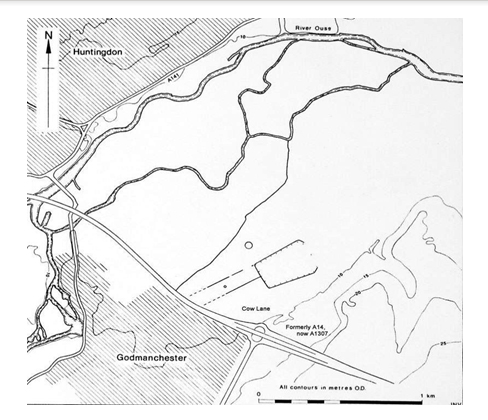

The route across the Common was classified as a public bridleway in the Godmanchester Enclosure Award of 1803.The earliest OS map – not a complete map, but a preparatory drawing of 1835 – shows it as a double dotted line (see far left on map), compared to Common Lane shown as a double solid line. The railway crossed the Common in 1847 and parts of its line were very close to the route of the bridleway. Maps of the mid-late 19C show just a single dotted line for the bridleway.

The bridleway continued in the 19C, presumably as a local route through the Hemingfords to Godmanchester and Huntingdon. In 1899 the young Virginia Woolf, was holidaying with her family at the Rectory in Warboys. She recounts in her diary the day they were to attend a lunch party in Godmanchester, but after missing their connecting train at St Ives, hired a pony and trap at The Fountain Inn to drive them there: we crossed the river over the lengthy and beautiful bridge and drove our five miles through quaint old villages – such as I have never seen equalled. Everything is old.

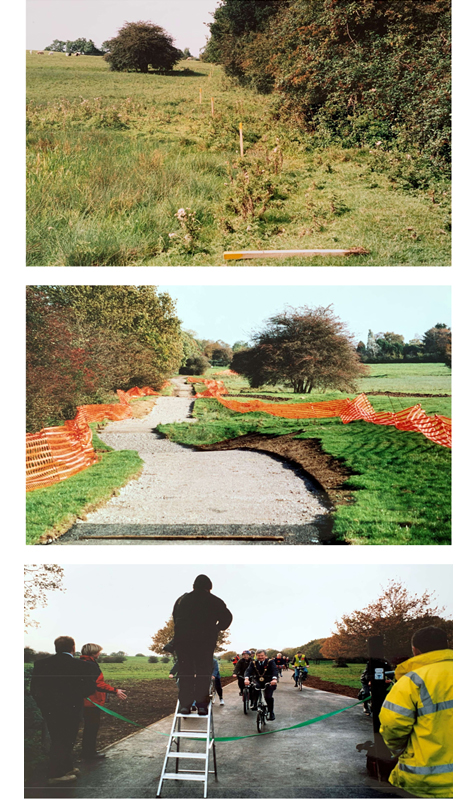

In the 20C and 21C bridleways have a predominantly leisure use. They exclude motorised traffic: they can only be used by horse riders, pedestrians and, since 1968, by cyclists who must give way to the walkers and horse riders. When the railway across the Common closed and its track lifted in 1962, people preferred to use part of its elevated bank with a hard surface as the route of the bridleway. Gradually, the number of cyclists increased and it began to be used as a commuter route to Huntingdon and the train station – safer and shorter than the A14, although dark and muddy in winter.

In 2004 Sustrans opened the Long Distance Cycle Route 51 from Oxford to Ipswich. Its route from Godmanchester to St Ives would use that of the bridleway and Ogilby’s road. Clearly the surface across the Common needed a significant upgrade to facilitate modern cycle tyres and wheels. A three-metre width tarmac path was constructed – and because this is part of The Hemingfords Conservation Area and also a Site of Special Scientific Interest, great care was taken that the new path was unobtrusive and folded sympathetically into the various undulations of the landscape. The Conservation character assessment notes: There is good ridge and furrow on the Common, much of which may be medieval, perhaps being formed before the area became permanent common pasture. Arguably, this may be the most extensive example of this kind of earthwork left in Huntingdonshire.

The Mayor of Godmanchester opened the new path and since then its use increases every year – commuters, long-distance cyclists and every grade of leisure cyclists plus walkers: the latter now outnumbered by the men and women in lycra. The cyclepath/bridleway is a wonderful facility and a pleasure for all to use.

When the cycle path was being constructed I took the photographs, as shown above, of work in progress. But I also poked around the diggings and was delighted to find a small flint tool – probably a scraper. Such implements are so tactile and fit perfectly into the hand somewhat eerily, when I reflect that it was probably last held in the Neolithic period 4000-6000 years ago.

Flint tools are not rare, and have been found in several areas of Hemingford Abbots, in particular one site at the western end of Common Lane where the previous householder regularly dug them up in his front garden. Over the years he amassed an impressive collection which has now been given to the Norris Museum. The new house on the site is called ‘Flint House’.

However, about 30 years ago there was news of discovery of an extraordinary rarity from the Neolithic period – and it was on Godmanchester Common. The Central Archaeology Service of English Heritage (now Historic England) undertook an archaeological excavation prior to gravel extraction on the site and it was funded by Redland Aggregates Ltd. Aerial photography had shown the significant potential of the site from ‘crop marks’ - dark lines which marked the position of underlying ditches.

Aerial photo of crop marks on the site. The view is looking west from the Common. Top left are the allotments on both sides of the road into Godmanchester from the A1307.

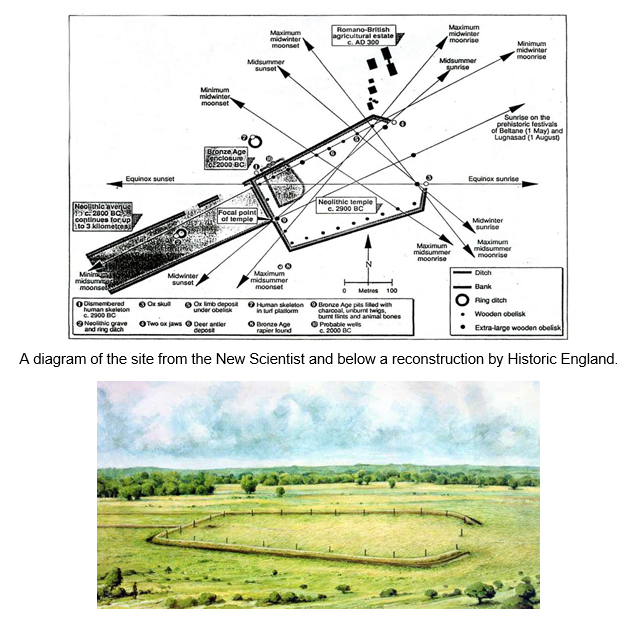

The excavation was carried out from 1988 – 1992 but in 1991 it became something of a sensation when an article was published in ‘New Scientist’ magazine with the headlines: Godmanchester’s temple of the Sun. It described the discovery of a ceremonial complex - a long cursus (an avenue) leading to a large trapezoidal enclosure formed by ditches and banks and containing 24 wooden obelisks positioned to give a variety of astronomical alignments. The New Scientist article overflowed with excitement: this site seems to be, astronomically, by far the most elaborate so far found in Western Europe. In terms of astronomical alignments, the Godmanchester complex is substantially more sophisticated and comprehensive than Stonehenge. A later paper by the director of the excavation, Fachtna McAvoy in 2000, set a more measured tone: The enclosure at Godmanchester is, however, without parallel in both the combination of [its] elements and the sheer scale of the work. (The cursus, with a bank and ditches, leading to the enclosure was c 90m wide and up to 3km long. The enclosure was 6.3ha in area.) It demonstrates, at the least, an ability to devise a geometric design and translate this into a groundwork with considerable precision, even without the possible incorporation of celestial alignments. Chronology was established by radiocarbon dating of charcoal from the wooden posts. This showed that the ceremonial centre was in use around 1200 years before the earliest Egyptian pyramids, 1000 years before the construction of the first Stonehenge and nearly 4000 years before the Roman occupation of Britain.

After the archaeological excavation, the site was dug for gravel and then used for commercial landfill. Nothing now exists of the monument except the archaeological record. As you enter Godmanchester from the A1307, pass the entrance to Cow Lane on the right, you will see a large earth mound beyond the allotments on the right. This was the site. The landfill site is now closed (i.e. full) and is about to be landscaped by the current management SITA Ltd. Working with Godmanchester Town Council, Godmanchester in Bloom and the adjacent Wildlife Trust Reserve they are organising planting schemes. There will be some public access when complete, and importantly information boards will be placed to recognise this unique historic site and explain what was once there.

As you will see in the New Scientist diagram, Bronze Age and Roman buildings were located close to, but not encroaching on, the site of the Neolithic monument. It was a complex multi-period landscape with archaeological remains of considerable importance. Central to it all was the Neolithic monument whose sophistication is still being evaluated. But for the layman, such as me, it is difficult to comprehend how such a building was constructed, when the necessary knowledge and data (especially the astronomical observations) had to be gathered and saved over years, possibly generations, and then collectively applied by peoples to whom we don’t attribute any form of writing or recording.

But especially, I observe that many people walked across this area of the Godmanchester Common in the Great Ouse Valley, first to build and then to visit the Neolithic monument. What route did they take? Those ancient footsteps may have been guided by a map of their own. For if those people of c 6000 years ago could chart the complexity of the orbits of earth and moon, they must have been able to follow the landscape. And thus, they and countless others have crossed this area for thousands of years.

References:

A Passionate Apprentice - the early journals of Virginia Woolf ,1990 Hogarth Press p148.

The Gordon map is in the Huntingdon Record Office; the Jeffreys map is in the Norris Museum.

Godmanchester's temple of the Sun, David Keys, New Scientist, 23 March 1991.

Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Landscapes of the Great Ouse Valley, Ed Mike Dawson, Council for British Archaeology, 2000. Acknowledgements and thanks to Godmanchester Porch Museum with Historic England for illustrations of: crop marks, reconstruction of the ceremonial site, and map of the site area.H

Hemlocs. www.hemlocs.co.uk