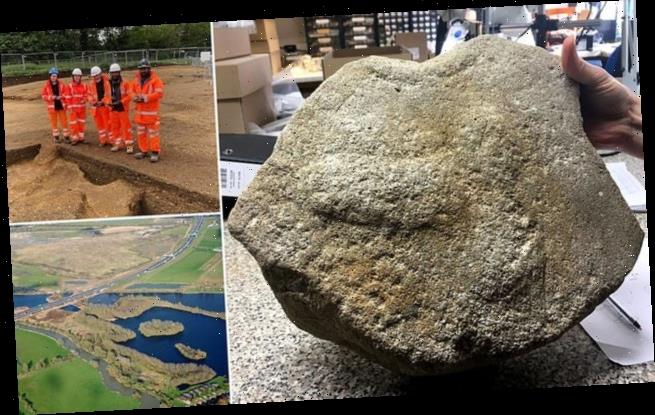

Kate Hadley, Curator of The Godmanchester Museum was presented with the stone by Quinton Carroll, Cambridge County Council’s archaeology boss and head of the Historic Environment Team. The millstone with its phallic image is part of a Roman magic system that regulated everyday life in ancient times.

Within that social map of magical regulation, this phallogenic stone promises protection from the evil eye or ill-wishing gods and also promotes bravery, wellbeing, fertility and protection to the grain and bread trade, both of which underpin the legal and trading functions of Roman society. Soldiers were paid in bread. Grain formed part of the Empire-wide Annona tax, but particularly powerful in Roman Britain.

Like many millstones, this has been imported from Derbyshire and a skilled artist stonemason has been employed to carve the phallus, so it is an expensive stone, a grand tool. It was found during the A14 excavations, in a high-end Godmanchester Roman villa, and one would assume belongs to a powerful owner.

Reconstruction by Professor Stephen Upex.

Mrs. Rachel Thurley, whose house in The Stiles today stands on the site of the Basilica, was used to her young son, Simon, and his friends digging up Roman objects in Godmanchester. Throughout the last century, children and adults all over town were acquainted with this excitement. Indeed, her friend, the late Gerald Reeve, used to take naughty children with him to dig in order to steady their behaviour and to help them concentrate.

Mrs. Rachel Thurley, whose house in The Stiles today stands on the site of the Basilica, was used to her young son, Simon, and his friends digging up Roman objects in Godmanchester. Throughout the last century, children and adults all over town were acquainted with this excitement. Indeed, her friend, the late Gerald Reeve, used to take naughty children with him to dig in order to steady their behaviour and to help them concentrate.

At that time, in the 1970s, the family lived in Chapel House next door to her current home. One day a child who was staying came in from the garden and brought her part of a hunt cup appliquéd with the figure of a huntsman. The huntsman’s bow and his quarry, the deer’s antlers, were done in fine barbotine work. She took away the trowel. She says, “It was obviously a fine piece, better we waited until Michael Green came. We knew there was something there in our garden space. After all, we lived on the Roman road.” The family lived on Roman Ermine Street, the main arterial link between London and Hadrian’s Wall which still crosses Godmanchester. It is now a small road or pathway and known today as The Stiles.

In his newly published book, Durovigutum, the late Michael Green’s entry for the discovery of the Basilica is dated 1971. He had seen the pillar fragment in Mrs. Thurley’s house and then found a third century major town building. It was massively constructed of Barnack ragstone and flint masonry with a pillared portico. It is suggested by Oxford Archaeology East that the capitol pillars in the Porch Museum, lent by them and found at Rectory Farm, were originally robbed from the Basilica in the late 4th century.

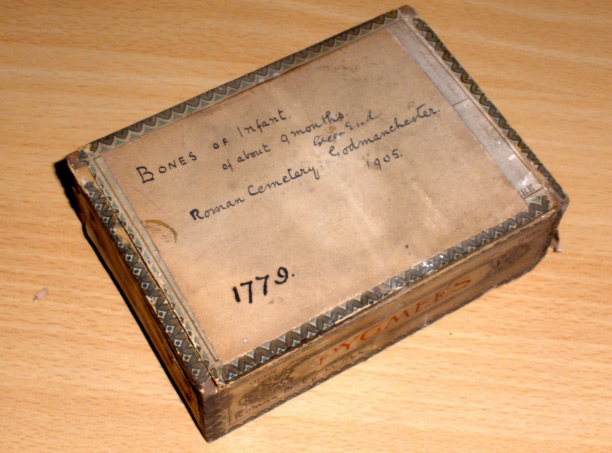

“Bones of an infant at about nine months, Roman cemetery, Godmanchester 1905”. The words were written in copperplate lettering on the slightly battered cigar box. It lay in an archive box amongst the remains of Roman pottery sherds. (i) Norris Museum volunteer Rodney Scarle was meticulously photographing and recording the large collection of Roman artefacts held at the Museum. He pointed out the box to me whilst we were chatting about his work. I asked whether I, as a biologist, could lay them out for photography.

The Reverend Walker’s box containing Roman infant bones, from 1905

I opened the box, and there, protected by cotton wool, were the small bones and fragments. I gently began laying them out on a piece of card. The task was complicated by the fact that the bones of infants and very young children do not look like those of adults. (ii) Our adult hip joints for example, are made up of several bones that fuse together.

On the one hand, it was obvious that not all the bones were present. On the other, there seemed to be duplication. If you look closely at the picture, you can see that bottom right there are at least three very robust long bones that are most likely to be femurs or thighbones. This suggests that we may actually have the bones of several infants mixed together. Even today, thighbones are used for estimating the age of an infant before birth and after. With lengths here of about 7 to 8 cm, these matched those of new-born infants. (iii)