When writing Martin Chuzzlewit in 1843, Charles Dickens posed the question, “Why do people spend more money upon a death, Mrs Gump, than upon a birth?' He was reflecting a trend that was also common in the previous two centuries. Many executors of estates spent a substantial proportion of the deceased's assets on a lavish funeral even for a relatively low status person. The funeral costs set out in this article may also be compared to the wages of the commonest occupation, an agricultural labourer, who earned about a shilling a day in the eighteenth century.

Seventeenth-century funerals were dignified occasions; filled with processions, tears, solemn (Jostures and lengthy sermons, but they were also occasions for feasting and the exchange of gifts. Much of the cost of a funeral was in respect of food and drink. Mourners were commonly fortified with beer, wine or spirits and they expected food and drink commensurate with the deceased's social rank. In Huntingdonshire, expenditure on food and drink for mourners varied widely and was not necessarily related to social rank. A barber from Godmanchester, John Dickenson had goods worth £47 15s when he died in 1676. His funeral cost over £6, more than the funerals of half the gentry whose records survive. Two thirds of the cost of Dickenson's funeral was spent on food and drink; bread and cakes £2 10s and a hogshead of beer £1 12s 6d. Although the amounts were small, the Overseers of the Poor in Godmanchester also provided beer for mourners even at paupers' funerals.

People could be buried in the most expensive lead coffins or their shrouded body might be placed in a reusable parish Coffin for the duration of the funeral ceremony. People of rank preferred their own personal coffins and "would not be seen dead' in the common parish box. Most Huntingdonshire probate records which provided details of funeral expenditure recorded a coffin. Coffins at the end of the seventeenth century typically cost ten shillings and there was little variation in prices. More than the bare minimum funeral was usually provided for paupers and in the three years 1787-9 the Overseers of the Poor in Godmanchester provided seven coffins most of which cost nine shillings each. In the eighteenth century, coffins were made of wood but covered with fabric, usually baize. Upholstery pins were nailed to the surface of the coffin in various patterns and the coffin was finished with stamped metal motifs which were cheap to produce. Coffins finished in polished wood did not become fashionable until the introduction of French polishing in the mid-nineteenth century.

The funeral ritual adhered strictly to the hierarchical niceties of genteel funerary decorum. The purpose of gifts of gloves and hatbands to mourners was to maintain perceptions of status. The most expensive funeral in the Huntingdonshire probate records at £106 5s 10d was that of a clergyman, Francis Barnard of Wyton in 1682. Barnard's coffin at £5 was ten times the common sum of 10s and his burial linen was a further £5. Gloves provided for mourners at Barnard's funeral cost £39 15s 8d. This sum is put into perspective by a comparison with John Berridge's funeral at Upton in 1722 when 14 pairs of gloves were provided at a cost of 1/- per pair. A horse and related charges for Barnard's burial was £413s whereas a horse for Francis Marchant's funeral at Stanground in the same year, 1682 cost only 10s.

Parish bells tolled when a person was dying and rang again when the funeral service took place. The tolling of the bell was variously interpreted by Protestant and Catholic but after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 it symbolised the rehabilitation of the ceremonies of the Church of England. The range of payments for bell ringing is illustrated in Huntingdonshire where the cost of digging James Cooper's grave and ringing the bell was 2s in 1681 whereas in the following year John Peachey a gentleman from Needingworth had ringers costing 10s. Bells also tolled for the poorest in society. In 1789, the Overseers of the Poor in Godmanchester provided beer costing 3s and 2s 10d for the toll bearers at the funerals of John Ray and a deceased person recorded as Bright.

Funeral sermons followed a set pattern. A text would be expounded to remind mourners of their own mortality and this would be followed by a biography of the deceased. The description of the character of the deceased was awaited with the keenest anticipation. The preacher carefully selected what was good from the person's life and drew a veil over the rest. In this way he could both satisfy the expectations of the congregation and his own conscience. Income from funeral Sermons was a lucrative business for the clergy. In Huntingdonshire, fees for funeral sermons were almost always 10s in the last quarter of the seventeenth century.

Washing, winding and watching were all involved in preparing the body for burial. Neighbouring women and female servants were frequently employed to clean and dress a Corpse. Winding of the Corpse in a sheet or a burial shroud was the minimum requirement for a decent burial for only animals were buried naked. Legislation during the reign of Charles II required all bodies to be buried in wool in order to support the domestic woollen industry. This is reflected in a number of payments in probate accounts where woollen cloth is expressly recorded. The woollen sheet for B Atkins of Holywell in 1681 cost as much as 18s whereas the woollen to wind the body of James Cooper of Stanground in the same year was only 6s. The custom of sitting up all night watching the body applied to both rich and poor. The intention was to safeguard the body and to ensure that there was somebody present if the corpse revived. In 1720, women were paid 2s 6d for laying out Henry Careless a waterman, from Godmanchester and a further 3s 6d was paid for watching the body, victuals and drink for the watchers and for the fire and candle.

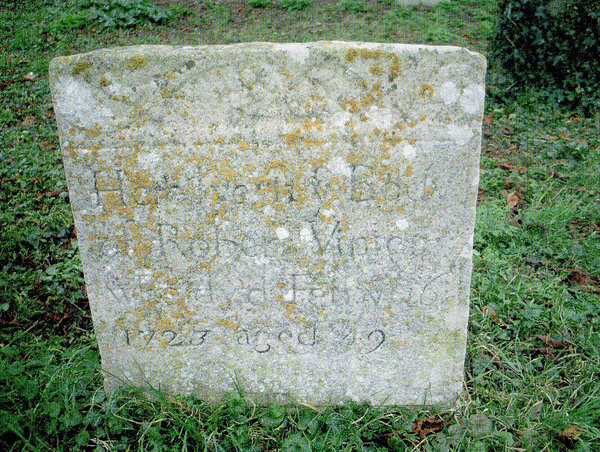

The usual place of burial was the Anglican parish churchyard. Although the unbaptised or suicides were not legally provided for even these were often buried in an unconsecrated part of the churchyard. The practice of erecting gravestones goes back to at least the medieval period although these were usually for high status individuals and survival of medieval gravestones is very rare. Few graves particularly in churchyards have tombstones before the late seventeenth century. In Huntingdonshire expenditure on headstones became much more common in the second half of the eighteenth century. Typical costs were between £1 and £1 10s. Tombstones were also erected for those of relatively low status. Henry Apthorp, a butcher from St Ives had a gravestone which cost £2 2s in 1783 and setting his gravestone was a further 6s 8d. His funeral cost £8.4s 9d, 41% of his assets. One of the oldest surviving gravestones in Godmanchester churchyard is that of Robert Winter a tailor who died in 1723. The inscription reads, "Here lyeth the Body of Robert Winter who dyed February 16th 1723 aged 49.

Gravestone of Robert Winter 1723

Vinter's goods were Valued at £34 8s 6d When he died. Perhaps saddest of all they included three barrels of beer in his buttery worth 16 shillings which he had not got round to drinking

KEN SNEATH